intro

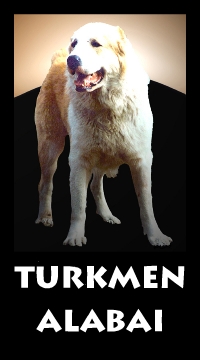

Strength and nobility are the main features of Turkmen dogs, alabies. Nobody knows when the first dogs appeared on the territory of Turkmenistan. However, it is known exactly, according to the bone relics from the sites of ancient towns, that in Turkmenistan during the Bronze Age several breeds of dogs were bred.On the site of ancient Anau (5 km to the west of Ashkabad) in the lower stratum of the New Stone Age, relics of the Indian wolf were found which differed from other wolves by its exterior and skull. Specialists connect these relics with the origin of the modern German sheep dog. In old Merv (Gaur-kala) a statuette of a sheep dog was also found. In settlements in the mid-Amu-Darya archaeologists found terracotta statuettes of hounds and shepherd dogs dating to the early Medieval Period. Dog bones found during the excavations in Khorezm of the 12th-14th centuries testified that the local dogs differed from each other by their types and sizes - from spitzlike dogs to small sheep dogs.

One of the ancient local breeds is a sheperd dog which the Turkmen people call alabais ("a skewbald" is the most popular color of the breed). The Turkmen legend, retold to me by the historian A.M.Annanepesov said that in ancient times the alabai females were taken away high to the mountain and tied with the lambs there. A snow leopard heard the lambs' cries and came down the mountains to mate with them. The largest alabais were descended from their offspring.

Aristotle wrote about eastern dogs, that they were descended from the interbreeding of dogs and tigers. Later he said more abstractly "...with any beast that looked like a dog."

The terracotta statuette from Altyn depe (2000 BC) gave the ancient image of the sheperd dog with cut ears and tail. Archaeologists consider that this is the image of the modern Turkmen alabai.

Some archaeologists state that the Tibetan mastiff is its ancestor. At present the Turkmen alabai is its direct descendant and it has not been influenced by other breeds.

The image of the enormous dog represented on the Parthian rhyton from Nissa (18 km from Ashkabad) is related to the mastiff breed. The breed of giant mastiffs was very popular among cattle-breeding tribes of Middle Asia. They were highly appreciated in the Ancient East The "Nissian mastiff" looked like dogs from Gandhara (the region in India) which were taken by Alexander the Great from Sopeifa. Sopeifa dogs were let go against the lions.

Probably, such dogs were used during the funeral ceremony of the mazdeists as watchdogs to look after the deceased person. The massagets used special dogs to eat corpses.

Later there was a dog cult among the Zoroastrians of Iran and Turkmenistan. In their opinion it would be a great misfortune for somebody if he offended a dog. If a man saw a homeless dog he had to bring it home and feed it. The dog chose itself whether it would stay at the home or go away.

In ancient times the alabais' ancestors were taken out to the Middle East. They were very popular in Ancient Assyria, Urartu and in Egypt. Egyptian and Assyrian reliefs show their images, similar to lions in size (as on the rhyton from Nissa). In the East, men hunted lions, tigers, wolves, and buffaloes with the help of these dogs. Later they appeared in Ancient Greece and spread in the countries around the Mediterranean Sea. In ancient Rome these dogs were used in the circus, in bloody performances. According to our facts all the mastiflike breeds descenoied from these dogs. Many of them greatly differed from the initial type of shepherd dogs of Middle Asia.

It was known that Huns (the Turkmen ancestors) took away the blind puppies from their mother's and the sheperds fed them themselves. The grown up dog remembered its caretaker and was faithful only to him. Such dogs were used for guarding sheep and house, for hunting and in the military service.

It was said that the Turkmen people didn't pay attention to the breeding of their dogs. However, from this point of view, it would be impossible to keep pure-bred and the image of the alabai's ancestor from the Bronze Age. The massive and broad cranial part of the head with high developed cheekbones, a narrow flat forehead, and a stupid muzzle are the main features, which allow us to come to the conclusion about the preservation of the pure-bred over centuries.

It was known that the Turkmen people did not write pedigree books and didn't register pedigree dogs in studbooks as they didn't do it for their famous Akhalteke horses. But they knew all the deserving representatives of the breed which were wounded in fights by bigger animals. It was enough to call the name of the dog's master and the dog's name, and the experienced shepherd could speak about the dog's pedigree and could its qualities and features.

Several times a year the Turkmen people held dog fights where the champion was announced. The bitches from distant regions were brought to these male champions for coupling. Their puppies were taken away on the 7th day. Their tails and ears were cut and the wounds were powdered with ashes. This ancient custom was practical. The parts that would be vulnerable in fights were reduced. Besides, cutting the ears led to improved hearing.

In the Kaahka etrap I observed another method of cutting the ears and tails: the sheperds would break the three-day old puppies' tender ear and tail cartilages. The bitch would lick the wounds of its young and the wounds closed up during two days. Month-old puppies were taught various commands. The main commands were: "hah" or "bas" ("crush" - ordered as the dog was unleashed to prey) "tap-tap" ("look for"), "alyp ber" or "ap er" ("take and bring"), "kiv - hai - hai" (ordering the dog to attack a wolf or snow leopard), "yets-e-bas" ("catch and press"), "ha-kush-kush" ("kill").

The puppies were taught only their master's commands and from their childhood they were trained for chasing wolves. Such dogs were not afraid of big animals and they learned their habits in fights. The true alabai's puppies were not afraid of grown dogs and didn't put their tails between their legs in a fright. Alabais differ from other breeds in Asia, and it is wrong to call them either Middle Asian or sheep dogs. Firstly, the breed of alabai is found only in Turkmenistan and doesn't correspond to other Middle Asian breeds.

Secondly, alabai lives in the pasture with sheep flocks to protect them. In some regions it is used for guarding herds of cows.

We should pay attention to the opinions of Russian scientists V.A. Kalinina, T.M. Ivanova, L.V. Morozova, who reject the breeding of the Middle Asian sheep dog as not corresponding to the essence of the alabai breed.

It is noted that within the breed there are different types which have no scientific appellations. In ancient times the Turkmen people divided internal breed types according to usage: "mergekchi" (wolf crusher), "grounchi" (sheep dogs), "sakchi" (a guard); also according to physical features: "kopek" (the most massive possessing muscular force and strong kick of the chest), "kopek-si" (less massive but having high speed) and the half breed of alabais with the Turkmen greyhound - tazy.

The alabai is a noble dog. It will beat a wolf to its last breath in a fight, whereas in a fight with other dogs, alabais will never exceed their opponent's limits. Alabais taking part in dogfights display brilliant techniques. The preparation of such a dog is similar to the preparation of a champion fighter. Before dogfights all dogs follow a particular regimen: rational feeding, massage, running, and swimming.

The Turkmen alabai has a strong nervous system which is the result not of evolution but of special selection. Turkmen sheperds rejected unbalanced dogs. Pure bred alabais never barked at random and never howled at nights.

Throughout the history of breeding there were always more male dogs than female. Only a notable female could give birth to a puppy. Fights were held among them; they were allowed to fight only once at the age of 6 months. The best bitches were selected for future breeding, taking into consideration their capacity for work and fighting.

Turkmen alabais were widely used in Uzbekistan, Iran, Tadjikistan, and Kazakhstan. Many countries of Eastern and Central Europe are actively engaged in the breeding of these dogs. The ability to adapt well is an alabai quality and they are trained easily.

The Turkmen alabais have taken part in exhibitions since 1930. At the All-Union exhibition in Moscow 1964 the bitch Aina won, and in 1971 at the International exhibition in Budapest the Turkmen alabai Karagoz got an excellent mark. Throughout Soviet history only the breed of Middle Asian sheep dog "altai" was awarded the first pedigree class and it was the only representative of this breed put down into the All-Union stud book for dogs. The best dogs worked guarding flocks and the dogs' masters didn't pay attention to the exhibitions. The definition of the breed's standards led to the breed's degeneration in Turkmenistan. Lately interest in the Turkmen alabai has been growing. The best representatives of this breed, having been bred in Moscow with other breeds, cost from US$2,000 to 3,000. At International exhibitions nobody pays attention to alabais training, awarding prizes only for their existence. The real pure breeds of alabais are in their motherland - Turkmenistan. There used to be hundreds of pure alabais; now there are only a few dozen left. Besides excessive export, there is a tendency to interbreed alabais with other breeds and it may lead to the disappearance of this breed.

In order to preserve this valuable breed, the government has stopped uncontrolled export. Alabai enthusiasts are making efforts so that this unique breed, having influenced many other breeds throughout the world, will never disappear.